When David Fincher‘s Battle Membership premiered in 1999, it met with sharp criticism from Child Boomer reviewers. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Solar-Instances labeled it “fascist macho porn,” whereas Rex Reed of the Observer dismissed it as completely devoid of redeeming qualities. But, a decade later, The New York Instances heralded Battle Membership as “the defining cult film of our time,” and Rolling Stone included it in an inventory of the 25 finest cult movies ever made.

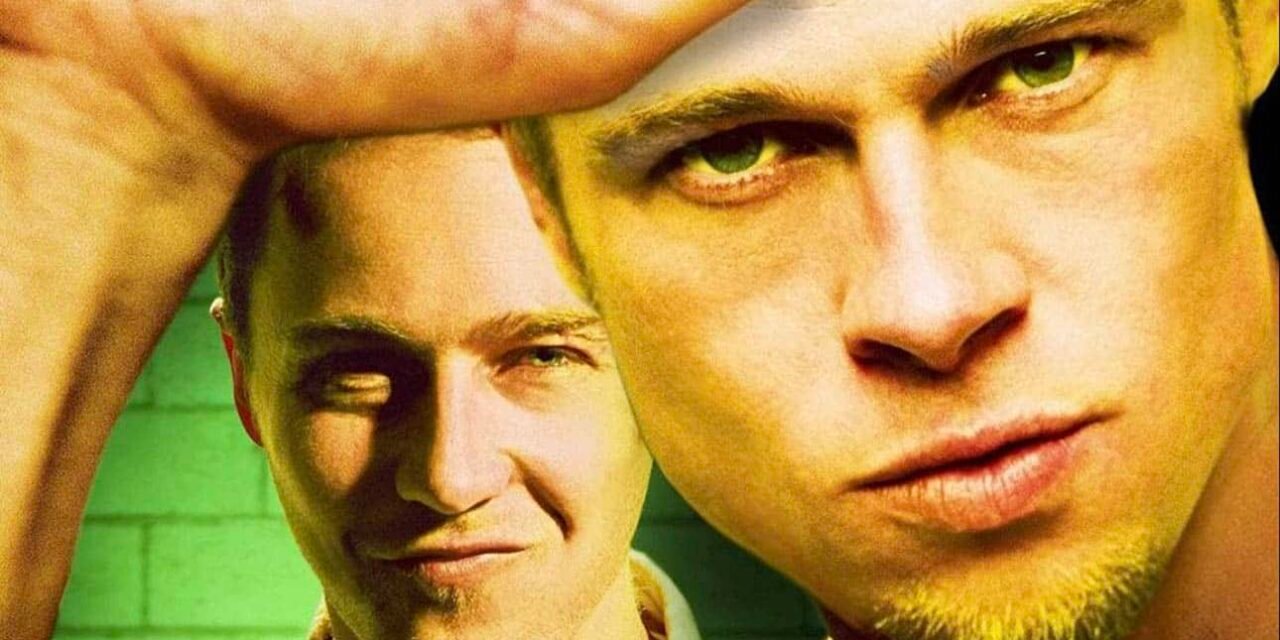

Clearly, Battle Membership was not focused at critics like Ebert and Reed. That is exemplified within the movie’s pivotal midpoint scene the place Brad Pitt’s character, Tyler Durden, strides throughout a dirty basement at Lou’s Tavern, addressing a motley group of battered Battle Membership members as “the center youngsters of historical past,” a pointed nod to Era X.

Past its sensationalism, Gen Xers—these born roughly between the mid-Nineteen Sixties and late Nineteen Seventies—earned the epithet of the “forgotten era,” typically eclipsed by the Child Boomers and Millennials. Raised in a tradition saturated with the empty guarantees of tv, they grew disenchanted with conventional values and established norms. This sentiment resonated deeply as a conservative rallying cry of the Nineteen Nineties, which many in Era X discovered laughable, particularly in gentle of non-public experiences such because the fallout from no-fault divorces.

Battle Membership emerged throughout this backdrop, reflecting quite a few various actions and subcultures of the Nineteen Nineties—grunge, psychobilly, and extra—all looking for connection and that means. Nonetheless, it approached the theme of subculture from a distinctly masculine perspective.

Adapting Chuck Palahniuk‘s 1996 novel, Battle Membership contains a narrator who, like many Palahniuk characters, dodges self-realization till suffocating coping mechanisms push him to a breaking level and he should confront the reality. Performed by Edward Norton, this unnamed protagonist, whom the movie conveniently permits us to name “Jack,” leads an insipid existence as a “recall marketing campaign coordinator” for an vehicle firm. His life is devoid of that means, symbolized by his sterile, IKEA-esque high-rise rental. Jack discovers he has no actual self-identity and has by no means crafted an genuine life.

Whereas Ebert and Reed’s era had movies like Mike Nichols’ The Graduate (1967), which portrayed paralyzing potentialities, Battle Membership flips that narrative. Jack exists in a actuality stuffed with expectations however no alternatives for transformation. In a satirical tackle the remedy tradition of the Nineteen Nineties, he briefly breaks freed from his isolation and insomnia by pretending to be a struggling particular person in help teams, which solely underscores his deep-seated need for one more identification and results in the arrival of the enigmatic Tyler Durden.

In a Jungian sense, Tyler represents Jack’s shadow-self—a manifestation of his unconscious that each the character and the viewers uncover by the movie’s conclusion. Jack’s existential disaster is so dire that he fabricates a savior, main him right into a tumultuous underworld. Durden epitomizes a distorted model of Nietzsche’s Übermensch, prompting Jack’s awakening by destroying the very rental that represents his empty way of life. Each characters share the commonality of getting grown up with absent fathers, main them to have interaction in bodily fight in opposition to each other and finally kind a bare-knuckle boxing membership the place camaraderie is constructed by violence.

Coincidentally, Battle Membership debuted the identical month Susan Faludi’s Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man was revealed, the place she scrutinizes the erosion of conventional American masculinity post-World Struggle II. Faludi argues that evolving gender roles, layoffs, and the feminization of labor have left modern American males adrift. This theme resonates by one in all Jack’s preliminary encounters with a former bodybuilder who has misplaced his testicles, additional accentuating the characterization of the emasculated man, juxtaposed with Jack’s obsession with IKEA furnishings and the bags handlers’ humorous misinterpretation of his electrical razor.

Tyler Durden then emerges as a hyper-idealized embodiment of masculinity, guiding Jack and the Battle Membership members towards reclaiming their primal nature. In a strong manifesto, Pitt’s character asserts, “We have now no Nice Struggle. No Nice Despair. Our Nice Struggle’s a religious battle. Our Nice Despair is our lives.” By way of shared violent experiences, a ritual akin to spiritual congregations, males confront their existential fears whereas cultivating self-definition, mirroring religious trials that promise enlightenment.

Nonetheless, Durden’s philosophy veers towards the intense with the creation of Challenge Mayhem. Whereas the movie considerably muddles its political undertones, Palahniuk’s novel factors out that modern males are burdened by historic violence, turning into “slaves of historical past” anticipated to “clear up after everybody.” The novel’s Challenge Mayhem immediately targets a museum, illustrating how the narrator’s era should study to harness “the facility to regulate historical past.”

The movie, in the meantime, retains the concept that the transition from pre-industrial to industrial tradition has stripped males of their identities, with Durden advocating for a “cultural ice age” that resembles a hunter-gatherer society. His followers have interaction in guerilla avenue theater and sabotage meant to dismantle fashionable socio-economic constructions, finally escalating to bomb-making that eerily foreshadows occasions like 9/11. Finally, Durden’s anarchic impulses coerce Jack to symbolically destroy part of himself to outlive.

As Battle Membership approached its launch in Fall 1999, twentieth Century Fox marketed it as America’s reply to Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996), leaving audiences puzzled. Critics likened the movie to Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971), debating its potential affect on disaffected younger males amid the looming anxieties of the millennium. But the movie’s standing advanced post-DVD launch, aided by burgeoning on-line dialogue platforms. Its unconventionality sparked a cult following that diverged from mainstream reception.

Furthermore, the movie encapsulated the last decade’s zeitgeist, formed by the rise of anti-government militias and figures just like the Unabomber, juxtaposed in opposition to actions just like the Promise Keepers and the Million Man March. Battle Membership has frequently lent itself to reinterpretation, resonating with actions like Occupy Wall Road in 2011 and even the alt-right resurgence. Few movies really feel as eerily prophetic as Battle Membership in relation to the January 6, 2021 Capitol riot, an occasion underscored by echo chambers feeding disenfranchised people a way of reclaimed energy. Gavin Smith of Movie Remark aptly described it in 1999 as the primary movie of the twenty first century—prophesizing its profound ongoing relevance.

But, regardless of its enduring influence, one should query whether or not a section of the male viewers failed to know what Jesse Kavaldo phrases “the Palahniuk paradox,” the place the narratives empower the disenfranchised male solely to humorously and morally critique him. Finally, although, many would nonetheless choose to embody Tyler Durden quite than Jack, regardless of the reminder that Durden is a fictional assemble. As Fincher elucidated in a 1999 interview, Tyler Durden “is every little thing you’d wish to be, besides… he’s not dwelling in our world.” Maybe that stark realization isn’t a foul takeaway from a movie typically dismissed as missing redeeming qualities.

Works Cited

Kavaldo, Jesse. “The Fiction of Self-Destruction: Chuck Palahniuk, Closet Moralist.” Stirrings Nonetheless: The Worldwide Journal of Existential Literature, vol. 2, no. 2. December 2005.

Keesey, Douglas. Understanding Chuck Palahniuk. College of South Carolina Press. September 2016.

Smith, Gavin. “Inside out: David Fincher.” Movie Remark, no. 35. September/October 1999.

Palahniuk, Chuck. Battle Membership. W.W. Norton. August 1996.